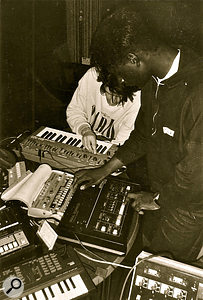

Graham Massey at Square One Studios, 1989.Photo: Lee Wrathe

Graham Massey at Square One Studios, 1989.Photo: Lee Wrathe

Born of the fertile late‑'80s Manchester music scene, 808 State's 'Pacific State' was a landmark in British house music.

"When people mention 'Pacific State', they often refer to the clarinet part without realising it's actually a sax,” says musician, composer, producer and engineer Graham Massey. "I was the one who played it, and that was because there were a lot of jazz influences in what 808 State was creating at that time. That record didn't just come from the house scene; it also came from jazz fusion and exotica.”

Originally recorded in 1988, 'Pacific State' was a landmark track in the development of UK acid house during the late '80s and early '90s. It helped to define the whole rave‑based 'Madchester' scene that centred around the Haçienda nightclub, run by Factory Records founder Tony Wilson, and also served as a major influence on future generations of techno and electronica artists.

Formative Experiences

Interested in astronomy and new technology while growing up in Manchester during the 1960s, Graham Massey developed a love of synthesizer music during the early part of the next decade. He was particularly taken with Stevie Wonder, as well as the progressive rock sounds of Hawkwind, Gong and Magma.

"I was familiarising myself with the names of all the different keyboards listed on the back of LP sleeves,” he recalls. "The EMS VCS3, RMI Electra Piano, Moog bass, Mellotron, ARP 2600... People were getting guitars, basses and drums, but you never even saw synthesizers in Manchester unless they were in a music store, and that meant they were still a thing of great mystery to me.”

While inspired by the Moog‑based sounds of John McLaughlin's Mahavishnu Orchestra and ARP‑based sounds of Weather Report, Massey began designing synth rigs in the back of his school exercise books after seeing Tangerine Dream play at a local venue named the Hardrock in 1975.

"I turned a cheap Woolworth's chord organ into my own fake Mellotron,” he says, "and a Rolf Harris Stylophone was my synth.”

Nevertheless, the first instrument that Graham Massey really learned to play was an electric violin. Hardly the easiest contraption with which to produce a listenable sound, so the fact that he taught himself was all the more remarkable.

"It's not like I was Jean‑Luc Ponty,” Massey remarks. "That electric violin was used as a sort of sonic weapon. I'd seen it being advertised for £12 on the notice board at Virgin Records and, when I bought it, it had been filled with roofing insulation, equipped with a contact mic and painted white, so it looked pretty cool. As it was an unusual instrument for a teenager to play, it was my passport for meeting other musicians at Manchester Grammar School and being invited to join a band called Aqua.

"The other guys were really into the music of Gong — a fairly odd Anglo‑French prog‑rock outfit that was known for its quirky music and funny time signatures — and we performed our first gigs in 1977, when punk was providing a great burst of energy in Manchester for people forming their own bands. The term New Wave meant all kinds of different things; one of which was that you could actually get by with limited musical skills and approach music in an anarchic, noisy way. I really got into the whole sonic aspect, and in 1979, I joined a New Wave band called Biting Tongues. It wasn't all that different to what I'd already been doing; I just had a different haircut in a group that had progressive roots but was going in a different direction.

"The great thing about those bands was that you could pick up any instrument and just have a go. So, while I mostly played guitar, I also played a bit of violin, a bit of trumpet, a bit of clarinet. Having seen bands such as Hawkwind, we were starting to think of music in a very textural way using tapes of found sounds playing randomly through our metronomic rhythm section. At the same time, cues were being taken from Krautrock and free jazz and spoken word. We'd all listen to The Faust Tapes [the 1973 album by Krautrock group Faust], which was very collage‑y, and that shaped our approach towards making musing by putting unusual combinations of sounds together. I therefore tried my hardest to play all of those different instruments, and those of us in the band had different skill levels — some were very skilled — but the whole notion of being a non‑musician was also an important idea at that time. So, even if I was only able to produce a screech out of a violin, that could be lovely! Especially with effects boxes on the end of it.

"What really lit me up was when we first went into the studio and were able to record the racket that we'd been used to making in some room. Now there was a second level of processing. Every studio in Manchester was full of AMS processing gear that would enable you to take the music a stage further by dressing it up and making interesting sonic statements, and that led me to want to get into audio engineering and be a 'studio‑head'. When sampling came along, that seemed like a really good fit for me — it was as if we could now do almost anything. Obviously, we couldn't, but that was the feeling when we first got our hands on samplers. They were unattainable machines for a number of years in the '80s — we'd hear about them, think about them, think about what we might do with them — until the [Akai] S900 and [Casio] FZ1 became available. At that point, we could exercise all of that stored‑up potential.”

A Mish-mash

The UK's first audio engineering school was Manchester's School Of Sound Recording, which opened in 1984 within the basement of the same Tariff Street building that already housed Spirit Studios. Soon afterwards, Graham Massey enrolled in a two‑year SSR course while honing his behind‑the‑board and tape‑looping skills through assorted studio projects.

Martin Price and Gerald Simpson, 1988.

Martin Price and Gerald Simpson, 1988.

"When we first started messing with computers, we had an Atari 1040, running Hybrid Arts SMPTE track software in conjunction with recording on tape to build layers,” he recalls. "I had a part‑time job at a nearby café while doing the engineering course, and across the road from there was a record shop called Eastern Bloc. The people there used to come into the café for dinner, as did the likes of John Peel, because it was a sort of social hub. While John would come to Manchester to comb the record shops for new material, some of the tapes produced on the engineering course would find their way into Eastern Bloc. Kids would bring their demo tapes to the record store and we would then take them into the studio to be produced by us.”

One of these recordings was by Gerald Simpson, aka musician/DJ/record producer A Guy Called Gerald, whose Jamaican roots informed his own music. Simpson's fascination with breakdancing, hip-hop, drum machines and tape editing had resulted in his formation of an outfit named the Scratchbeat Masters with in‑your‑face teen rapper Nicholas Lockett (aka MC Tunes).

"Gerald did the musical side of his thing with early Roland gear such as the TR808 drum machine, SH101 synthesizer and TB303 bass synth,” Massey recalls. "Anyway, we decided to record together, and the first record we made featured a collection of different hip-hop groups as well as Eastern Bloc's owner, Martin Price. It was a kind of 'Pump Up The Volume' sampler recording — it didn't have any rapping on it, but there were about 18 people in the studio, all stuffing anything they could think of into the sampler while trying to bang the record into shape.”

The resulting 'Wax On The Melt' 12‑inch single was, according to Graham Massey, "an awful mess of a record”, but it served to bring together a set of artists who subsequently began performing hip-hop concerts around Manchester.

"Back then, apart from a few bands, there wasn't much of a hip-hop culture in Manchester, and no real club scene to perform that music,” he now says. "Most of it took place in youth clubs and community centres, and so Eastern Bloc gave it an indie edge and fused a lot of cultures together. People in that shop who listened to Public Enemy and Big Daddy Kane stood alongside those who listened to the Smiths and New Order. It was a cultural mish‑mash, and various influences were rubbing off on one another.

"There were naff electro records and cool electro records; naff hip-hop records and cool hip-hop records; naff house music and cool house music. For us, the cool house music was acid house — it didn't have that baggage that some of the Chicago house music had in terms of the lyrics and bluesy piano chord progressions. I wasn't particularly interested in that kind of house music. I was much more into this alien‑sounding house music that really fitted in with my alternative musical background. I connected with it.

"When we started playing acid house music at the hip-hop clubs it was terribly unpopular; the wrong place and the wrong time to do it. Nevertheless, things soon shifted to where all we eventually played was acid house. During the late '80s, there were a lot of shifts going on, not only because of the political and cultural changes in the world due to the ending of the Cold War, but also because of the changing technology which was ending up in our hands. We didn't have any money, but the new technology enabled us to speak a more international language.

"The reason an 808 was a cool thing to have is that it sounded like all that stuff from New York and it also sounded like a New Order record. In fact, New Order sounded worldly wise because they'd transcended the Manchester sound by recording with sequencers in New York. That's what the new technology did for them, and the sound was therefore really attractive to us because it would enable us to transcend who we were. I mean, it may sound cool to say you were in a band in Manchester back in the '80s, but back then it wasn't, because you never escaped. You wanted to branch out, but you really didn't have much hope of getting on the radio, and you really didn't have much hope of playing outside Manchester, London or Liverpool. But then, in the late '80s, things seemed to start moving quite quickly. Suddenly, it was easier to make records, it was cheaper to make records, and you could get them on Radio 1.”

Furthermore, Mancunian artists had a great resource in the form of Tony Wilson. One of the co‑founders of Factory Records — with a roster that included Joy Division, New Order, Happy Mondays and Orchestral Manouvres In The Dark — Wilson also managed the Haçienda when 'Madchester' was at its height, in addition to hosting a local arts programme on Granada TV. Graham Massey, Martin Price and Gerald Simpson appeared on the show in the guise of newly formed hip-hop outfit Hit Squad Manchester. The same trio also appeared as 808 State, between recording their debut album, Newbuild, at Spirit Studios in January 1988 and releasing it on Price's Creed Records label that September.

"Those appearances were amazing for us,” Massey confirms. "They really lifted us up and people started offering us gigs. It all happened super‑quick. Whereas before we'd had to slightly suppress our individuality, our music now had a context and we knew what we were making it for. It was almost un‑suppressable. Then again, the three of us were coming from three different musical directions and backgrounds, so the results were bound to be quite intense.”

Equipment used on the Newbuild album.

Equipment used on the Newbuild album.

When I ask Massey about the intra‑group dynamic and how they blended together inside the studio, he frankly replies, "I'm not sure we did! Martin was very much the head producer, saying 'We're going to make this happen,' while being full of ideas about the kinds of records he wanted to make. Gerald was hot on the technology — he knew the equipment inside out and recorded the hit acid house single 'Voodoo Ray' by himself before we did 'Pacific State'. He'd knock out tapes all the time, and my image of Gerald at that time is of him never, ever not having his headphones on. Usually, he'd be studying what he had recorded to cassette in his bedroom and he was pretty obsessed with the creative process. I, on the other hand, was making records based on MIDI technology and trying to continue what I'd been doing for a number of years. So, even though people treated me as the engineer, I was also the most traditionally musical member of the group in terms of sorting out melodies and what might be in tune.”

Newbuild

Newbuild, created over the course of a weekend in January 1988, was 808 State's first attempt to make an acid house record.

"Studio time was really precious, so the momentum was huge and we didn't hang about,” explains Massey. "We just threw a load of stuff on tape, incorporating various multitrack experiments. There were three SH101s running live, using the triggers from the 808 into the 101s and then sequencing on the 101s' little sequencers to make bass lines or top lines or mid lines. The 101s fulfilled each of those roles.

"The 303 was also really important, and on a couple of tracks we tried to integrate the MIDI technology, but not very successfully for writing in melodies. In fact, some of the melodies were played in freehand. We always had a problem sync'ing the Roland gear, because some of it wasn't MIDI, and it was only after Newbuild that we started to sync more successfully using a Korg KMS 30 MIDI synchronizer, with DIN Sync providing a 24 or 48 pulse‑per‑quarter‑note signal. It took a while for us to get that together.

"On Newbuild, we layered some of the sequences so they were in different times. A track like 'Flow Coma' had threes against fours, giving it a very polyrhythmic density. We had never heard acid house records that were so tangled, and back then that was obviously exciting for us. Some of the material on that album was stuff that Gerald had done at home with the 303 and some of it was completely improvised. We could program things like the drums outside the studio and then we'd be put in triggers independently; it really was a bit of a jam and some of the tracks were more together than others.

"We had an early Akai sampler in the studio — pre‑S900. It was a rack unit, and you could trigger that with a pulse or a rim shot from the drum machine. You could also alter the beginning and the end of it on a lever; do the sample start points. So, for instance, the vocals on 'Dr Lowfruit' and 'Compulsion' were done in the sampler, and we could really start messing with the trigger points and stretch things. That was terribly exciting back then, before we had time‑stretch — 'This sounds fab!' We also had various boxes to make all manner of electronic percussion sounds — if we had something, we'd stick it in. We'd never go, 'Oh, this needs more space.'”

The highly innovative house music on Newbuild would prove to be such a huge influence on electronic composer‑musician Richard James, aka Aphex Twin, that in 2005, a year after releasing 808 State's 1988 acid house cover of the New Order club anthem 'Blue Monday' on his own Rephlex Records label, he would also re‑release the aforementioned album. "It was the next step after Chicago acid, and as much as I loved that, I could relate much better to 808 State,” Aphex Twin told Mojo magazine. "It seemed colder and more human at the same time.”

The 1989 incarnation of 808 State: (standing) Darren Partington, Martin Price, Andy Barker, Graham Massey (seated) at Spirit Studios.

The 1989 incarnation of 808 State: (standing) Darren Partington, Martin Price, Andy Barker, Graham Massey (seated) at Spirit Studios.

Newbuild was followed by 808 State's first 12‑inch EP, Let Yourself Go. Meanwhile, another acid EP, featuring the tracks 'Massage‑a‑Rama' and 'Sex Mechanic', was released under the pseudonym Lounge Jays. Both songs would later be reissued by Rephlex as part of the Prebuild LP.

Quadrastate

"John Peel played the Let Yourself Go tracks a lot on the radio,” Graham Massey recalls, "and then he asked us if we wanted to do a session for his show. We were supposed to go to Maida Vale Studios in London to do that, but we asked him if we could instead make it where we normally made our records, because we didn't fancy working with BBC engineers and going back to that old‑fashioned protocol. It's not the way we made records. Well, he managed to get that quite far down the line, which is unusual with the BBC, but at the last minute, because of union rules, they pulled the plug on that idea and said we had to use their own facility, which we never did.

"Based on the promise that we'd be allowed to do the session at Spirit, we had already started recording a couple of tracks there, and they became the starting point for Quadrastate. So, when we first recorded some of the parts for 'Pacific State', that's what we had in mind — we weren't making something for release, but for a BBC session.”

The control room at Spirit Studios housed an Amek TAC Scorpion console, Otari 16‑track one‑inch machine, Tannoy Gold speakers and Yamaha NS10 nearfield monitors.

"The combination of that desk and that tape machine produced a very fat sound,” Massey says. "I didn't realise it at the time, but it had a distinct sonic imprint. And while there was a window to the main live area, we never went in there — we were always in the control room. In fact, quite often there were quite a lot of people with us in the control room. Recently, I was talking with somebody who remembered being at one of the sessions for 'Pacific State' and he told me, 'There were about 12 people in the studio when you were doing the sax part.' I thought, Yeah, he's right! It was a Saturday morning, people used to pop in and hang about, and it was a bit of a social scene thanks to the Eastern Bloc shop being just around the corner. They'd turn up, drink coffee and sit about.”

Unlike the Newbuild album, the Quadrastate EP — comprising 'Pacific State', '106', 'State Ritual', 'Disco State', 'Fire Cracker' and 'State To State' — took far longer than a weekend to record.

"After we got a bit of a profile from Newbuild and Let Yourself Go, we started to do more concerts while also making radio and TV appearances,” Massey explains. "So, we were recording when we could, which was based on not only having the available time, but also the available money.”

Gerald Simpson and Graham Massey collaborating again for an acid jam as Rebuild.

Gerald Simpson and Graham Massey collaborating again for an acid jam as Rebuild.

'Pacific State' and 'State To State' were the tracks that, according to Graham Massey, were initially worked on for the John Peel session that evolved into the Quadrastate EP. In both cases, improvisation was the name of the game.

"We didn't have the equipment at home to write material, so the only time we could write as a group was when we were in the studio,” says Massey. "At that point, we were going to the Haçienda and various parties, and a massive record was Marshall Jefferson's 'Open Your Eyes'. Whenever it was played, this atmosphere kind of overtook the room. It had to do with the chords, the ecstasy culture and the song's tropical warmth. You could see that warmth and togetherness on people's faces. It was the sort of vibe we wanted to capture for 'Pacific State', so we sampled up some chords on a Juno 106 — when you put the chorus on it and put on loads of filter so that it's quite muted, you get that warm atmosphere, and we sampled that into a Casio FZ1 keyboard as a chord: one note on the keyboard would play that chord, and the same chord was played on a Roland D50 using the 'warm strings' preset. The pad sound was therefore a combination of those two things layered, with some additional filtering on the FZ1.

"The drums on 'Pacific State' were actually from a 909, not an 808, and the clap pattern's quite important on it. It's pretty unusual. Also, to add to the sort of tropical nature of things, we added the bird sound from the Akai library that came with the S900. It's called 'Canadian Loon'. Then the track hung about for a fairly long time until the 101 bass line added a nice feel.”

Indeed, this melodic, constantly fluctuating bass line is one of the elements that marks out 'Pacific State' as different to conventionally structured techno recordings that have melodic parts layered over much shorter, repeating bass lines.

"It didn't have a defined, minimal bass line, but a snaking 16th-note bass line,” Massey concurs. "Having octaves in it gives it a certain amount of syncopated funk. Because we did it on the 101, which has no memory, we should have written it down, but we didn't, and so when we redid it for later versions we had to re‑imagine the bass line everytime we went in the studio. That means the first bass line has been lost and all subsequent versions were different.”

"I was not a real saxophone player but I could crank out a melody, and I think my limited ability made it what it was. If I had jazzed off, it would have lost it. Instead, the four notes I could play were set over the chords to provide a kind of signature."

"I was not a real saxophone player but I could crank out a melody, and I think my limited ability made it what it was. If I had jazzed off, it would have lost it. Instead, the four notes I could play were set over the chords to provide a kind of signature."

Sax Solo

Meanwhile, another unique element adding to the atmosphere of 'Pacific State' is the soprano saxophone that serves as a counterpoint to said bass line.

"We toyed with the idea of vocals, which would seem like the normal thing to do,” Massey continues. "However, we didn't really know any good singers or agree on a subject that might work for the lyrics. At that point, I was still recording with Biting Tongues, which had turned from a normal band into a sort of electronic duo with a jazz‑influenced saxophone front line. Howard Walmsley, who played the sax in Biting Tongues, had left his soprano from a session the night before, and so I picked it up and just had a go. I'd played the clarinet and was a bit of a have‑a‑go saxophone player, but I was not a real saxophone player. Still, I could crank out a melody, and I think my limited ability made it what it was. If I had jazzed off, it would have lost it. Instead, the four notes I could play were set over these chords to provide a kind of signature, and then, for a 'B' section, we made a sort of kalimba section that was actually sampled off the 909 drum machine.

"Some people find it surprising that there's a sequencer in the 909. You can run the drum machine as is, but there's also an internal sequencer, and for 'Pacific State' this created a swing feel. We'd always exploit the swing because drum machines can be quite boring, and so if any little techniques could be thrown in there — like stopping it on odd amounts of numbers, doing half bars or whatever — we'd always try to add a bit of sophistication.”

Endless Variations

After the version of 'Pacific State' that kicked off Quadrastate was completed in 1988, it was then re‑recorded for the single issued in November of the following year once 808 State had signed to ZTT. By then, Gerald Simpson had departed to pursue a solo career, keyboardists Andrew Barker and Darren Partington had both been recruited, and sessions for the band's second album, 90, were taking place at Square One Studios in Bury.

"The Radio 1 DJ, Gary Davies, heard the original version of 'Pacific State' on the Quadrastate EP, and he started playing it on his daytime show,” recalls Graham Massey. "Then, when ZTT got involved, Trevor Horn was totally into this radio‑edit idea of making the perfect seven‑inch single. So, we had a lot of discussions about trying to make a much more structured radio‑friendly record. I'm now not sure whether that was right or wrong, but we were playing ball because we'd agreed to the new record deal and were listening to the advice being offered.”

The seven‑inch single released by ZTT became known as 'Pacific – 707', whereas yet another, third version — again completely re‑recorded, this time at Square Dance Studios in Stoke — was titled 'Pacific – 202'. Subsequent remixes included 'Pacific – 303', '0101', '212', '516' and '718'. Not that Graham Massey, who still performs alongside Messrs. Barker and Partington (and who reunited with A Guy Called Gerald for some live acid house jams in 2012 under the name Rebuild), has a particular preference for any of them.

"I've been playing that song for about 25 years and it's so weird in my head,” he says. "At the time we did the various recordings, I didn't over-think it. But now that it's viewed as somethingof a classic, I'm kind of forced to see it in a different way. The feedback has always been positive from people for whom it's got a very profound meaning. Well, I'm a fan, too, but not necessarily of my own music. I'm a fan of other people's music. Still, everytime I perform 'Pacific State' I try to do it differently in order to get something out of it. It's a great track to improvise on when we do concerts; we've stretched it into all kinds of shapes and I've found ways of re‑loving it, if you know what I mean. It's actually quite jazzy now, and although some people may not like that, it at least gets me through.”